Unpacking Bonnie and Clyde's Endless Pursuit of Happiness on the Road

- Natalia Cuadrado

- Mar 2, 2021

- 6 min read

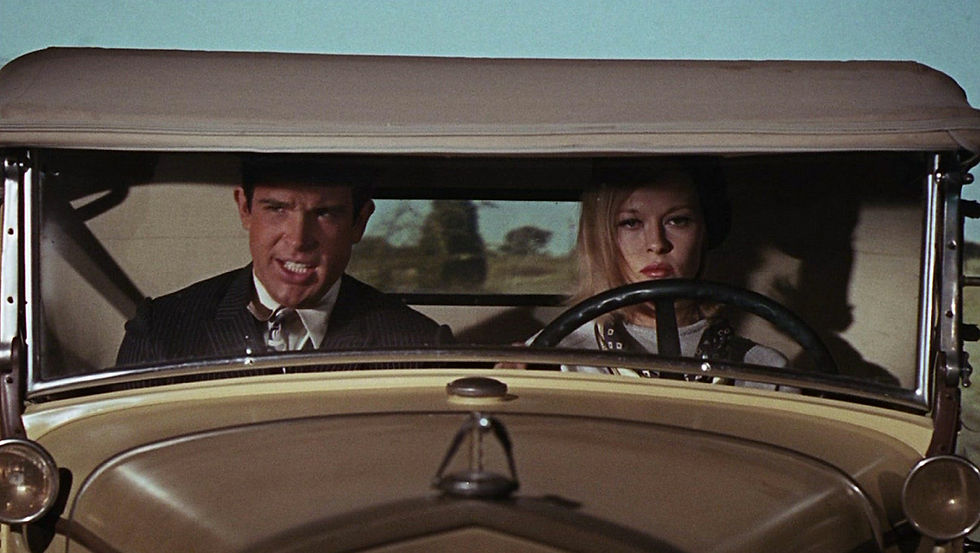

Director Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde (1967) serve both as a landmark film that set a precedent for what we’ve come to know as the New Hollywood, and as the embodiment of a suppressed desire for success and freedom. A drive that – as suggested by Robert Warshow’s essay “The Gangster as a Tragic Hero” – is deep into the American psyche. This notion can be translated into the endless pursuit of happiness that is promised to citizens, but that’s never actually fulfilled and thus results in the inevitable failure that optimism itself helps to create. This article will analyze how the myth of the journey on the road is exemplified throughout the story of Bonnie Parker (Faye Dunaway) and Clyde Barrow (Warren Beatty) in Penn’s classic Gangster Film.

While one can argue characters like Bonnie and Clyde are mere fictional figures

created with and for literary or cinematic purposes, that could never be the case for the

much-celebrated motion picture, as it is based on true events. The film explores the

voyaging of Bonnie, an attractive young woman living in the early 1930s mid-southern

America, as she finds herself bored, restless, and stuck with the rural conventional life

when she meets Clyde, a rebellious ex-convict with a masculine attitude and physique,

but clumsy demeanor. We’ll never actually know how the real Bonnie and Clyde were,

however, the characterization of the film’s leading figures could very likely come from

the famously immortal pictures taken of the real leaders of a criminal band, who even in

real-life was come to know as populist anti-heroes.

The characters' desire for an out-of-the-ordinary pursuit is evident from the first

scene and on. The movie begins with a sensual shot of Dunaway’s character, who serves

as much more than a sex symbol throughout the film, which is part of the script’s transgressional tone against the social values of the time. This particular scene is

handcrafted with a series of carefully framed jump cuts that introduces the motion picture’s European influence. What writers David Newman and Robert Benton did was adopt a screenplay about a story that took place during the Great Depression, in a way that would appeal to audiences in the conservative society of the 1960s. They could only achieve so in the style that they did by fashioning something daring and exciting, never seen before, at the time, on the movie screens.

“When an American movie is contemporary in feeling, like this one, it makes a

different kind of contact with an American audience from the kind that is made by European films, however contemporary”, argued Pauline Kael in the famous essay that

changed the way critics saw the film. It can be inferred that she was right, as Newman

and Benton were followers of the French New Wave, a style that deconstructed the

American classic way of doing cinema to bring something new to the mix on the

European screens.

It didn’t turn out to be a coincidence how the masterminds behind the script

incorporated techniques of their favored style by recurring to fast cuts and paving the way

for abrupt shifts in tone, as well as the film’s distinguishable banjo music. All in order to

construct the rural setting of the early 30s that awakens the nostalgia in some spectators

and, in turn, introduces younger audiences to a Depression-era narrative that feels

distinctively and passionately American. Spectators today are still won over by what,

back then, was an unprecedented sensual and visionary cinematic experience.

The viewer can ever so relate to the visionary ambitious Barrow Gang

—composed by Bonnie and Clyde themselves, as well as by Clyde’s older brother Buck

(Gene Hackman); his wife, Blanche (Estelle Parsons), and the gang’s sidekick C.W.

(Michael J. Pollard) —as seekers of fame and adventure, that are brought down by a

grim reality in the most brutal and violent way possible. “Newman and Benton have been

acute in emphasizing this—not making them victims of society (they are never that, despite Penn’s cloudy efforts along these lines) but making them absurdly ‘just-folks’

ordinary”, wrote Kael.

Audiences feel a rush of excitement as they witness the characters go up and down

a road they could only dream about, for they know what the inevitable final destination

is, even if the ride seems tempting and fun. It’s just like what Warshow explains in his

essay, “the gangster is primarily a creature of the imagination. The real city... produces

only criminals; the imaginary city produces the gangster: he is what we want to be and

what we are afraid we may become.”

Despite this, one can’t help but root for the group who, after committing the

unspeakable, hop on stolen cars and head for the road who they foolishly but hopefully

see as the escape for a better life. “The film deploys road travel extensively as an

instrument of social critique and rebellion” (Laderman, 45). For they, essentially, not

only run away from the crime scene but from a way of life that’s imposed upon us by

every social construct that makes up our imagination.

Furthermore, as they make stops along their pathway, they come across the harsh

economic conditions of the time. That’s how Bonnie and Clyde’s famous phrase “we rob

banks” gets a metaphorical meaning, for they rob banks because bank robs people and

they’re the people. The pair become folk heroes as they show sympathy for the ones who

have been stripped from their dignity and their basic human right to pursuit happiness. Likewise, the couple is admired for having the courage of daring to aspire the

unattainable.

“Another way in which Bonnie and Clyde associate driving with liberation is by

developing sympathy with the average working person” (Laderman 45). Thus, they get respect, instead of pity, even though people —even Bonnie herself —know that they’re doomed. “I will send flowers to their funeral”, says an old man who the pair spared and told him to keep his money during a bank robbery in the film. All the while, Bonnie foreshadows and acknowledges what their unavoidable end could be, further

mystifying the tale of Bonnie and Clyde.

Someday they’ll go down together;

They’ll bury them side by side;

To few it’ll be grief—

To the law a relief—

But it’s death for Bonnie and Clyde.

The poem comes off as a crucial element for the duo’s mystique, sensual, and at

times like that, poetic lives. It is precisely the title characters' optimistic take on their very

own lifestyle that keeps the audience on the edge of their sits hoping, somehow, things

could turn out victorious for the gang because it would mean things could be possible for

them too. “Characters who transgress social laws and bounds through road travel

represent an alternative to society’s conventions” (Laderman, 43). Nonetheless, if they

ultimately end up paying the capital prize for having the gut to choose a forbidden path,

then, in a way, it would make the spectators feel at ease with themselves. Because if the

gangster, the one the imagination creates, can’t make it without danger lurking around, no

one can.

However, this doesn’t stop people from feeling sympathy and aiding the tragic

heroes when in need. One of the most compelling moments of the closet o

two-hours-long film is when C.W. takes the wounded couple to a zone of homeless

people who, in recognition of the couple’s good deeds in favor of the less fortunate, share

with them the little that they have to eat and drink. This is the scene when Bonnie and

Clyde’s folk heroism is manifested and, at the same time, understood by audiences who

conclude they would’ve done the same.

Nevertheless, as a Gangster Film, Bonnie and Clyde's message stands in that the

road of rebellion leads nowhere but fatality. In an instance, Bonnie laments in a kind of

regretful way how they’re back to being stuck. “We used to be going somewhere, now it

seems like we’re just going”, she tells Clyde. The candid moment suggests that, after

living through the struggles of life inside a getaway car searching for something, Miss

Parker just wants to settle down as she was always taught she should aspire. However,

this feeling is inevitable as long as the individuals seeking an alternative vision live

within a conservative society.

Wherever they go, the Barrow Gang seems to be bound by the extreme traditional

social values that impose so much but give so little. This is the subversive form that the

film took at the moment of its release, and it is as well what has made the motion picture

transcendental through the decades. Though some might say the thematic was ahead of

its time, the story seems to repeat itself over again through American history, serving as

an explanation as to why the classic feels so relevant and pertinent even today.

This gangster film’s sociopolitical critique, violent graphicness, and sensual

complexity made it possible for later films to further explore the genre beyond what was

once its classical take. Penn’s cinematic masterpiece is also considered innovative for its

time as it emerged along with another popular genre of the era, the Road Film. Whose

themes and allegories are teased throughout the whole film, as the getaway car takes a

form of its own and becomes a character that represents the happiness and freedom that

only the road can provide.

The major demise of trying to reach success seems to be only experienced through

characters like Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow, who, as outlaws, dare to seek their

ambition-driven-dreams by committing criminal acts that ultimately prove the journey to

be nothing more than the tragic and self-conscious myth. The downfall of the sensual

criminal pair comes in true French New Wave style.

One minute the viewer experiences the last of the movie’s sense of freedom — as

Bonnie and Clyde drive through an empty road back to their hideout in what feels like the

a most blissful moment of the film — and the next, they find themselves viscously

ambushed in a slow-motion bloody massacre choreography performance that both shock

and mesmerize audiences with a brutality that sends them back straight to reality.

Comments